Hammurabi ruled ancient Babylonia and a good part of the Mesopotamian basin. The code of laws attributed to him is one of the earliest and most comprehensive of such law codification efforts.

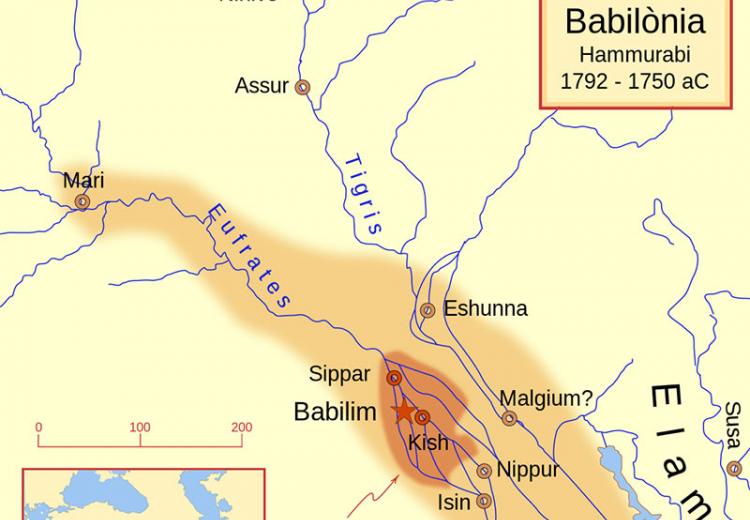

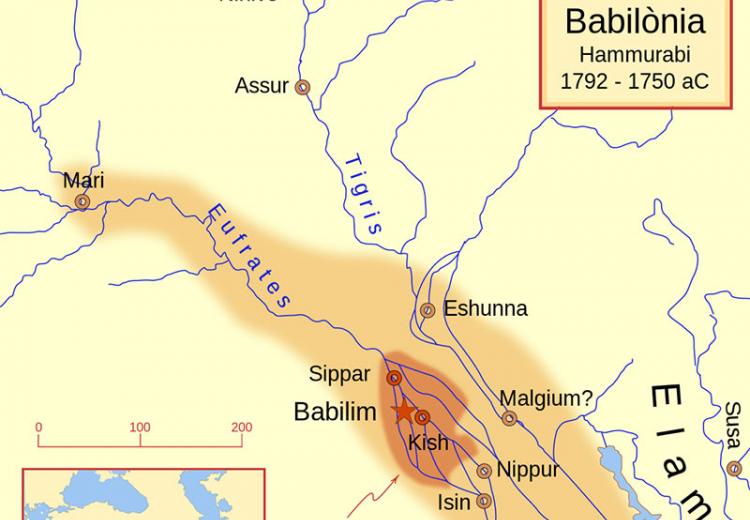

King Hammurabi ruled Babylon, located along the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, from 1792–1750 BCE. During his time as king he oversaw a great expansion of his kingdom from a city-state to an empire. However, today he is most famous for a series of judgments inscribed on a large stone stele and dubbed Hammurabi's Code. Scholars are still debating its precise significance as a set of laws, but the Code's importance as a reflection of Babylonian society is indisputable. In this lesson, students learn about life in Babylonia through the lens of Hammurabi's Code. This lesson is designed to extend world history curricula on Mesopotamia and to give students a more in-depth view of life in Babylonia during the time of Hammurabi.

What can we learn about Old Babylonian society from Hammurabi's Code?

How has Hammurabi's Code influenced subsequent codes of law?

To what extent does Hammurabi's Code still influence how we create and enforce laws?

Investigate Hammurabi's motives for creating and distributing his "Code."

Evaluate how Hammurabi's Code reflects Babylonian society at the time.

Assess the extent to which Hammurabi's Code remained relevant beyond his death.

Subjects & Topic:In the 18th Century BCE, Hammurabi (also spelled Hammurapi) became the sixth ruler in the First Dynasty of Babylon. The success of Hammurabi's military operations expanded Babylon north along the Tigris and Euphrates and south to what is now called the Persian Gulf. The empire he created is known as Babylon, while the civilization is often referred to as Old Babylonia.

The Code of Hammurabi, inscribed on a large stone stele-an upright slab--was uncovered by a French expedition in 1901. Its leader, Father Vincent Scheil, translated the code the following year. At the time, it was the oldest known set of what appeared to be laws. Since that time, however, earlier similar "codes" have been unearthed. Though Hammurabi's Code is not unique, it is still the longest code yet discovered and one of the only ones known to have been inscribed on a stele. Information and an image of the stele can be found by visiting the Louvre Museum, which is available through EDSITEment-reviewed resource The Oriental Institute: The University of Chicago. Once on the Louvre website, click on the link for "selected works" at the left; then, click on Oriental Antiquities; under "selected works" click on Mesopotamia and Anatolia; and finally, you will see an image of the stele by scrolling down through the thumbnail images. It is marked as the "Law Codex of Hammurabi." You may access directly the information about the stele, which is also from the Louvre.

The complete text of Hammurabi's Code is available from the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource the Avalon Project.

For a representative sample of the Code, read: the prologue (first and last paragraphs); precepts 3, 4, 60, 108, 196, and 228; and the epilogue (paragraphs 1–3 and 5). In the prologue, Hammurabi claims that his authority comes directly from the gods. He also states that the purpose of the Code is "to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land … so that the strong should not harm the weak." The third precept indicates the existence of a judicial system with elders serving as judges. The fourth precept indicates that fines of money and/or grain were imposed and implies the existence of something akin to our civil suits in which the complainant received a settlement. Number sixty indicates the existence of something akin to a sharecropping system in which one person farms land in exchange for land in five years. Such a system would tend to redistribute land from large to small owners. Number one hundred and eight indicates that women could own at least some kinds of businesses in Old Babylonia. Number one hundred ninety-six is perhaps the most famous of the precepts. It is also found in the Hebrew Bible (Exodus 21:18–19, 22–25, Leviticus 24:17–21) and in the Gospels (Matthew 5:38). Finally, number two hundred twenty-eight shows the specificity of the precepts and implies that there was a set fee schedule for the work of skilled tradesmen, in this case a set fee of two shekels for each sar of building, comparable to modern builders who charge so much per square foot.

The epilogue states that the stone on which the Code is inscribed was set up in the E-Sagil temple in Babylon. It informs the reader that through these precepts one can find out "what is just." In the third paragraph, Hammurabi pledges his allegiance to the god Marduk-the highest in the Babylonian pantheon, comparable to Zeus in the Greek pantheon. The fifth paragraph advises future kings to follow these precepts.

Content StandardsNCSS.D2.His.1.6-8. Analyze connections among events and developments in broader historical contexts.

NCSS.D2.His.2.6-8. Classify series of historical events and developments as examples of change and/or continuity.

NCSS.D2.His.3.6-8. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to analyze why they, and the developments they shaped, are seen as historically significant.

NCSS.D2.His.4.6-8. Analyze multiple factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.5.6-8. Explain how and why perspectives of people have changed over time.

NCSS.D2.His.14.6-8. Explain multiple causes and effects of events and developments in the past.

NCSS.D2.His.15.6-8. Evaluate the relative influence of various causes of events and developments in the past.

NCSS.D2.His.16.6-8. Organize applicable evidence into a coherent argument about the past.

PreparationIn this activity, students will begin to hypothesize what may have influenced Hammurabi's reign in Babylonia. In this exercise they will use what they have learned about Mesopotamia in the classroom, as well as the information presented here, in order to imagine what might prompt a ruler to write an organized set of rules.

Students will participate in a simulation in 3–5 groups. Each group will play the role of a council of advisors to King Hammurabi. They will meet to plan their advice to the king. Then, one or more representatives from each group will report their advice to the king. Groups should remember that Hammurabi is an absolute ruler and the consequences of a presentation that displeases the king could be severe.

This activity serves to establish an anticipatory set for what is to follow. Its purpose is to stimulate student thinking about the reasons behind Hammurabi's Code. How Hammurabi's Code actually reflects life in Old Babylonia will be the subject of the following activities.

In the hypothetical speech below, Hammurabi invokes some of the Babylonian gods (Anu Bel, Shamash), as he does in his Code. The Babylonian god Marduk was the chief god of the city of Babylonia. As a result of Hammurabi's expansion of the empire, Marduk also began to be considered the chief god of the entire traditional Mesopotamian pantheon. Religion was central to everyday life in Babylonia. Large temples were central features in every city and wealthy homes likely included their own private chapels.

Begin by informing students that Hammurabi became the sixth ruler in the First Dynasty of Babylon in the 18th Century BCE. The success of Hammurabi's military operations expanded Babylon north along the Tigris and Euphrates and south to what is now called the Persian Gulf. The empire he created is known as Babylon, while the civilization is often referred to as Old Babylonia.

Students may also be interested in seeing where the borders of Babylonia fall in terms of the Modern Political Map through a comparison with Mesopotamia in 1750 BCE, both available through a link from The Oriental Institute: The University of Chicago.

In this exercise Hammurabi has gathered his councils of advisors together. He (i.e. the teacher, presumably) will deliver a short speech, which is available here as a PDF. Groups are to frame their advice on the basis of the information provided in the speech and from what they will have already learned in class on Mesopotamia.

Allow time for the groups to meet and then present their recommendations. When these are done, conduct a brief discussion.

Now share with the class the brief section on Babylonia from the British Museum's Mesopotamia site's Introduction to Mesopotamia, accessible through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource The Oriental Institute: The University of Chicago. This will clarify what actually happened during Hammurabi's reign.

Begin this activity by showing students the Large Image of Hammurabi's Stela, available through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource The Oriental Institute: The University of Chicago. Tell the class we have quite a bit of information about this ancient stele, which you will share with them later, but, for now, you want them to consider the object itself. Without revealing anything more specific about the stele at this point, tell the students the original, though the only one in existence, is thought to be one of many. It is a stele, made of basalt (a hard black volcanic rock), standing taller than seven feet and measuring about six feet around at its base.

Think about large public objects with which students might be familiar, such as the statue of Lincoln at his memorial. Have them think about the following questions:

Ask students to look carefully at the stele. There is an image at the top and an inscription underneath. In this exercise students will be hypothesizing what the meaning of the stele might be. Have students describe the image at the top of the stele and then answer the questions about the stele available as a PDF.

The monumental size of Hammurabi's stele dramatized the king's power. The graphic on the stone communicated Hammurabi's message that the gods, the ultimate source of justice, provide legitimacy for his authority. A second reading of the meaning of this stone may be found in the possibility that the image communicated to viewers that Hammurabi's position was one of an intermediary between the human world and the world of the gods.

As ancient communities grew larger, they needed a stronger central government to complete and take care of necessary public projects -- such as the canals that enabled Babylon to grow surplus foods -- and to maintain law and order for keeping life in cities running smoothly. We know from records on clay tablets that Babylonia had an organized justice system. Such a system requires some standardization of the law as well as an educated class to serve as judges and court recorders.

Let the students know that some current books and websites still contain claims that Hammurabi's Code was the first set of laws ever made. But we now know that Hammurabi's was one of many codes created before and after his reign.

The existence of ancient codes such as Hammurabi's reflects a body of common law; yet collections of royal judgments were not codes of law as we understand the concept. They never served as a source of precedent when courts rendered decisions. Many scholars now consider Hammurabi's Code part of a longstanding tradition of public display of representative royal pronouncements. The precise intention behind the inscription on Hammurabi's Stela remains unclear. After the students become more familiar with the contents of the code, they will be given the opportunity to form their own hypotheses.

Prepare the students to read excerpts from the text of Hammurabi's Code by sharing the essay Law and Government from The Oriental Institute: The University of Chicago.

Students will soon work independently with a few of Hammurabi's pronouncements. The following discussion gives the students a general impression of the full text of Hammurabi's Code (Annotated) from the EDSITEment-reviewed website Avalon Project at Yale University. This should enable the students to appreciate the context of the excerpts they will read on their own.

Begin by reading the first and last paragraphs of the preamble with the class. Next, work through the following questions:

In order to give the students a general overview of the pronouncements, ask the class to work on the following questions and tasks:

Hammurabi's Code ends with an epilogue, a concluding statement. Read with the class the first three paragraphs (starting near the end of the first paragraph with the words "That the strong might not injure the weak") and the first sentence of the fifth paragraph.

Now the students can begin to form their own hypotheses about the purpose of Hammurabi's Code. Ask students to point to parts of the code that reflect the following possible reasons for its creation, design, and placement:

What other possible reasons—if any—for the creation of Hammurabi's Code and its public display might be indicated by the text?

Ask the students to each write a one-sentence hypothesis as to the purpose of Hammurabi's Code. The hypothesis might begin with the following words:

Ask students to share some of their hypotheses with the class. If desired, attempt to arrive at a class consensus in one sentence.

Much about Babylonia can be learned from the precepts (rules or instructions designed as a guide) in Hammurabi's Code. To model for the students what they will be doing later and to introduce some information about daily life in Babylonia, share with the class the following information:

Now share precepts #215-217. Which precept appears to apply to which class (the amelu, mushkinu, or wardu)?

You may wish to begin by having read the Lecture: The Code of Hammurabi and the section Mesopotamian Civilization available through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource Internet Public Library. Divide the class into five groups. Each will report back to the class what they have inferred about their assigned aspect of Babylonian civilization during the time of Hammurabi. Students should be directed to the EDSITEment Study Activity for the Activity, where they should click on the link to their group's worksheet which will form the basis of their presentations.

In their presentations to the class, students should point to the specific precepts from which they derived their conclusions. If desired, groups can use the chart, “Chart for Gathering Information from Hammurabi's Code,” which is available as a PDF, while gathering information.

Once the groups have presented, help the class generalize what life was like in ancient Babylonian society as a whole during Hammurabi's reign. What information indicates:

Students construct inquiry questions to investigate topics relevant to daily life in Babylonia and today. Based on independent or group research, students consider the relationship between these daily practices and Hammurabi's Code. Students use multimodal technology platforms to create original demonstrations of learning on any of the following topics and topics they personally choose and research:

Assign small groups. Each group will create a script for a hypothetical Babylonian trial based on one of the precepts from Hammurabi's Code listed below. Challenge the groups to include information about Babylonian society that they have learned in this lesson in the script. Make inclusion of such information an important part of your evaluation of the presentation. For example, the group would reveal some information about the status of women by simply making one of the witnesses a female tavern owner.

Choose from among the following precepts around which to create a courtroom scene: #9, 122, 125, 135, 142, 168, or 233.

Lesson Extensions