If there’s one thing every tech company has in common, it’s this: users.

Whether you’re Google’s search engine, serving a billion active monthly users who interact with your service for free, or Salesforce, with 3.75 million paying subscribers, building a technology product means serving people.

And in today’s always-on world, people’s expectations—for free and paid services alike—are high. Speed. Uptime. Useful UX. Today’s user base expects everything to meet a high standard.

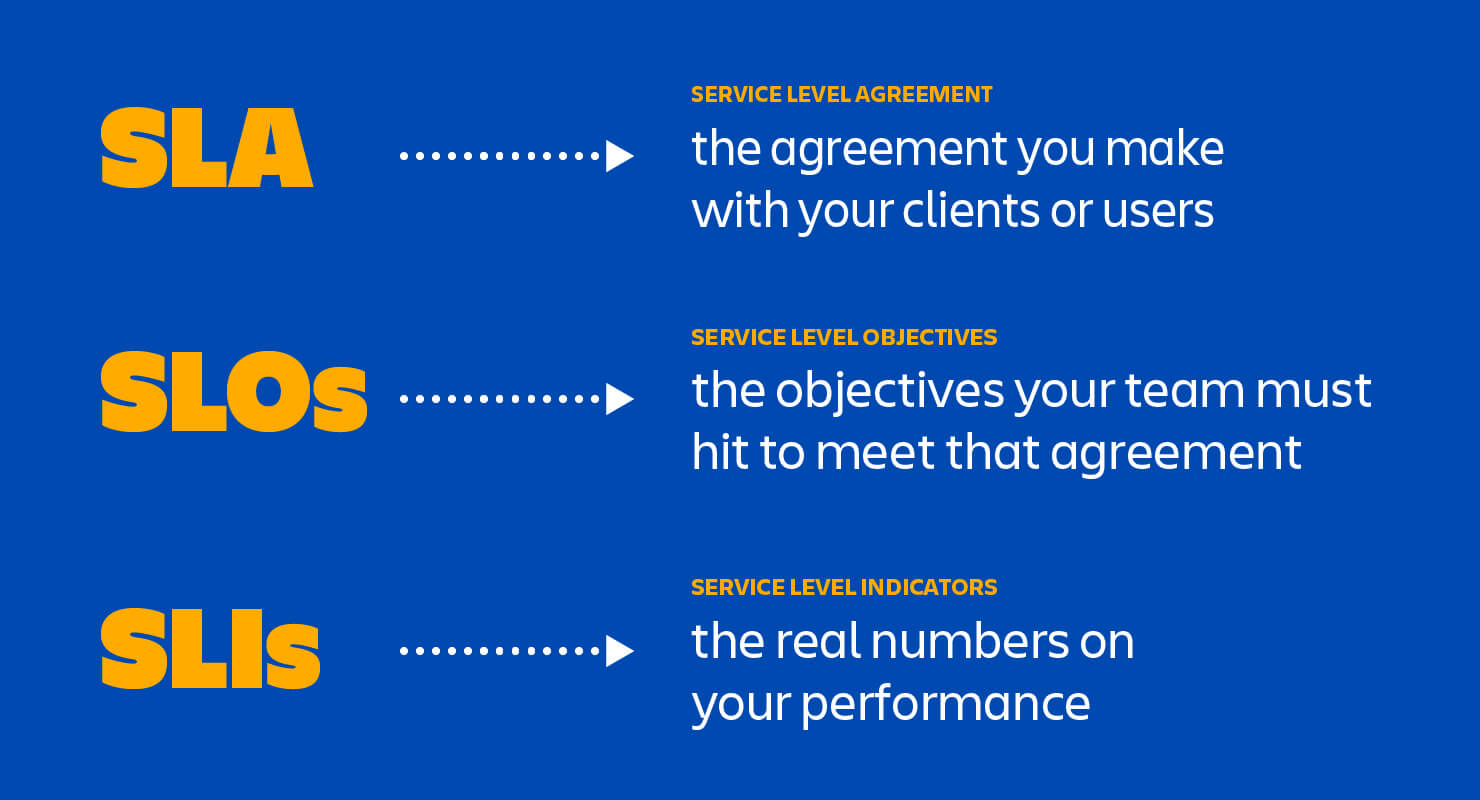

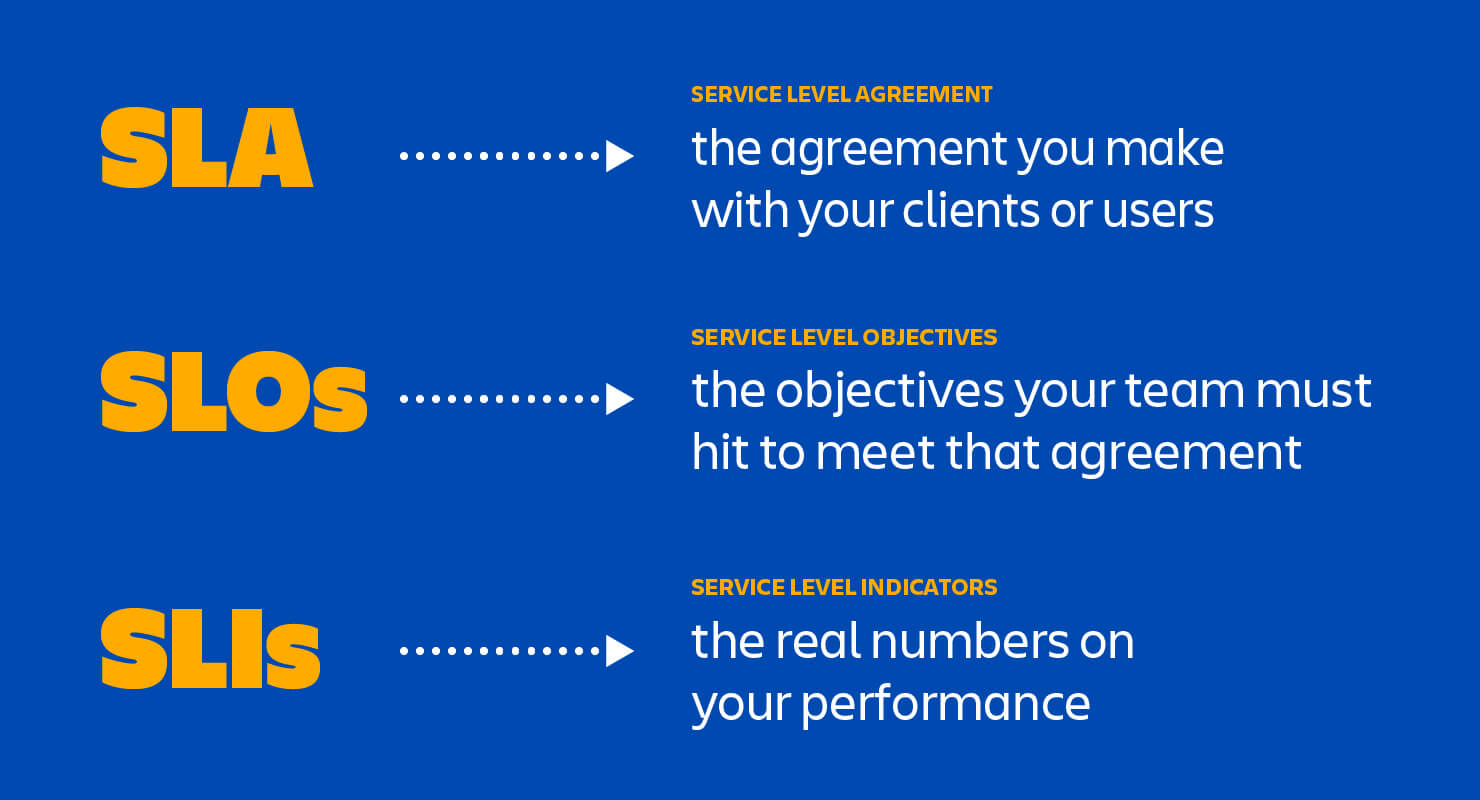

Which is why it’s important for companies to understand and maintain SLAs, SLOs, and SLIs—three initialisms that represent the promises we make to our users, the internal objectives that help us keep those promises, and the trackable measurements that tell us how we’re doing.

The goal of all three things is to get everybody—vendor and client alike—on the same page about system performance. How often will your systems be available? How quickly will your team respond if the system goes down? What kind of promises are you making about speed and functionality? Users want to know—and so you need SLAs, SLOs, and SLIs.

An SLA (service level agreement) is an agreement between provider and client about measurable metrics like uptime, responsiveness, and responsibilities.

These agreements are typically drawn up by a company’s new business and legal teams and they represent the promises you’re making to customers—and the consequences if you fail to live up to those promises. Typically, consequences include financial penalties, service credits, or license extensions.

SLAs are notoriously difficult to measure, report on, and meet. These agreements—generally written by people who aren’t in the tech trenches themselves—often make promises that are difficult for teams to measure, don’t always align with current and ever-evolving business priorities, and don’t account for nuance.

For example, an SLA may promise that teams will resolve reported issues with Product X within 24 hours. But that same SLA doesn’t spell out what happens if the client takes 24 hours to send answers or screenshots to help your team diagnose the problem. Does it mean the team’s 24-hour window been eaten up by client slow-downs or does the clock start and stop based on when clients respond? SLAs need to answer these questions, but they often fail to do so—a fact that has created a lot of animosity toward them from IT managers.

For many experts, the answer to this challenge is, first and foremost, that tech should be involved in the creation of SLAs. The more IT and DevOps collaborate with legal and business development to develop SLAs that address real-world scenarios, the more SLAs will start to reflect key realities, such as clients delaying their own issue resolution.

An SLA is an agreement between a vendor and a paying customer. Companies providing a service to users for free are unlikely to want or need an SLA for those free users.

An SLO (service level objective) is an agreement within an SLA about a specific metric like uptime or response time. So, if the SLA is the formal agreement between you and your customer, SLOs are the individual promises you’re making to that customer. SLOs are what set customer expectations and tell IT and DevOps teams what goals they need to hit and measure themselves against.

SLOs get less hate than SLAs, but they can create just as many problems if they’re vague, overly complicated, or impossible to measure. The key to SLOs that don’t make your engineers want to tear their hair out is simplicity and clarity. Only the most important metrics should qualify for SLO status, the objectives should be spelled out in plain language, and, as with SLAs, they should always account for issues such as client-side delays.

Where SLAs are only relevant in the case of paying customers, SLOs can be useful for both paid and unpaid accounts, as well as internal and external customers.

Internal systems, such as CRMs, client data repositories, and intranet, can be just as important as external-facing systems. And having SLOs for those internal systems is an important piece of not only meeting business goals but enabling internal teams to meet their own customer-facing goals.

An SLI (service level indicator) measures compliance with an SLO (service level objective). So, for example, if your SLA specifies that your systems will be available 99.95% of the time, your SLO is likely 99.95% uptime and your SLI is the actual measurement of your uptime. Maybe it’s 99.96%. Maybe 99.99%. To stay in compliance with your SLA, the SLI will need to meet or exceed the promises made in that document.

As with SLOs, the challenge of SLIs is keeping them simple, choosing the right metrics to track, and not overcomplicating IT’s job by tracking too many metrics that don’t actually matter to clients.

What will you do when downtime strikes? If you don’t already know the answer to that question, the default answer will be “waste precious time figuring out what to do.”

The better your incident response plan, the quicker and more effectively your teams will handle incidents. Which is why the first step of any new incident management program should be process and planning.

Any company measuring their performance against SLOs needs SLIs in order to make those measurements. You can’t really have SLOs without SLIs.

Every part of your customer agreement should be crafted around what matters to the customer. On the back end, an incident may mean addressing 10 different components. But in the client’s view, all that matters is that the system functions as expected.

Your SLAs and SLOs should reflect this reality. Don’t overcomplicate things by drilling down to a granular level and making individual promises for each of those 10 components. Keep your promises confined to the high-level, user-facing functionality. This will keep clients happier and less confused and simplify the lives of IT pros responsible for making good on your SLA promises.

Clients won’t always ask for clarification, so if your SLA language is complicated, you’re probably setting yourself up for some painful misunderstandings down the line. The simpler your language, the less likely client conflict is in your future.

Not every metric is vital to client success, which means not every metric should be an SLO. Commit to as few SLOs as possible and focus on the ones that matter most to customers.

Similarly, tracking performance on 10 components for each of 10 SLOs can get unwieldy very quickly. Instead, strategically choose which metrics actually matter to your core SLOs and put your energy into tracking those effectively.

What happens when the client is the one slowing down time to resolution? If you aren’t clear on this in your SLA, your team may be held to the impossible standard of resolving client issues without client involvement.

Leaving room for failures not only protects the business from SLA violations and hefty consequences, it also leaves room for agility—for the team to make changes quickly and have the space to try innovative new solutions that might fail.

Google actually recommends using leftover error budget for planned downtime, which can help you identify unforeseen issues (e.g. services using servers inappropriately) and maintain appropriate expectations from your clients.

Just because your team can probably maintain 99.99% uptime doesn’t mean that 99.99% should be your SLO number. It’s always better to under-promise and overdeliver. This is especially true for agile teams who want to launch early and often and need an error budget to keep up that quick pace.

For those of you following Google’s model and using Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) teams to bridge the gap between development and operations, SLAs, SLOs, and SLIs are foundational to success. SLAs help teams set boundaries and error budgets. SLOs help prioritize work. And SLIs tell SREs when they need to freeze all launches to save an endangered error budget—and when they can loosen up the reins.

Stay on top of SLAs to resolve requests based on priorities, and use automated escalation rules to notify the right team members and prevent SLA breaches with Jira Service Management.

In this tutorial, we’ll show you how to use incident templates to communicate effectively during outages. Adaptable to many types of service interruption.

An incident postmortem, also known as a post-incident review, is the best way to work through what happened during an incident and capture lessons learned.